|

Introduction:

It is a great honour to be here speaking to you today about the

Headwaters Project. First I would like to congratulate Surrey

Council on the leadership you have shown in addressing problems

ranging from air that is hazardous to our health to housing prices

that are beyond the reach of our average families. You were the

first city in British Columbia to require retention ponds for

stream protection, the first city to systematically adjust street

standards for reduced costs and for enhanced pedestrian and bicycle

comfort as shown in the 1997 Surrey Local Road Standards Review.

You were also the first BC municipality to propose a Small Lot

Zoning bylaw. Surrey leads the region and even Canada and North

America in these initiatives; and other communities, such as the

City of Vancouver, the City of Burnaby, and the City of Coquitlam

are following Surrey’s lead.

In December 1998, the City of Surrey Department of Planning and

Development agreed to enter into partnership with our research

group, a team of consultants, and a multi-constituent advisory

committee (involving various levels of government) in order to

produce a model capable of applying sustainable principles and

alternative development standards “on the ground”. The model that

developed is the East Clayton Neighbourhood Concept Plan (Figure

2). The basis for developing this model was a set of seven principles

for creating sustainable communities that had emerged from previous

joint projects between Surrey and the James Taylor Chair. The

first of these joint efforts was the first James Taylor Chair

Design Charrette for Sustainable Urban Landscapes, held in South

Newton area of Surrey. The design brief for this was developed

using existing local and regional policy directives for sustainable

development, such as the Growth Strategies Act, the GVRD Livable

Region Strategic Plan, and other local policies guiding more concentrated

growth. Each of the charrette teams were required to accommodate

a community of approximately 10,000 (similar to the projected

population for East Clayton) in ways that provide a variety of

housing, commercial and work places, while also preserving, or

even enhancing, the sensitive stream systems that surround the

South Newton area (Figure 3).

This project led

to the 1998 Alternative Development Standards for Sustainable

Communities workshop and publication, in which the James Taylor

Chair undertook research to demonstrate the costs and benefits

of alternative development standards, with a specific focus on

green infrastructure. Among other things, this research demonstrated

that incorporating stormwater management within the rights-of-ways

of an interconnected street system could reduce infrastructure

costs. It also demonstrated how alternative developments could

result in an up to one-third reduction of infrastructure costs

for a single-family home over the same unit in a conventional

cul-de-sac development. In January 1999, Surrey City Council authorized

planning staff to explore the application of seven principles

that emerged from these projects as the basis for developing the

Neighbourhood Concept Plan for the community of East Clayton.

Together with City staff, the James Taylor Chair and Pacific Resources

(guided by the Headwaters Advisory committtee), undertook an extensive

democratic design process that produced the East Clayton Land-Use

Plan and NCP (Figure 4). The Land-use plan was approved in November,

1999, and staff have been finalizing the NCP, which, we anticipate,

will be presented to Council sometime in December. Even at this

stage, there is remarkable interest in the Plan, both from within

the region, and throughout North America.

Before speaking directly

to the Plan and the seven principles, the following provides a

brief summary of a few of the issues that precipitated this initiative.

Currently, Canada

is not making its commitment under the Kyoto Convention to reduce

greenhouse gases in order to improve air and water quality (Figure

5). As a partial consequence of the way we build our communities,

people are being forced to drive more than they need to or even

want to. As the graph shows, the closer we move to the target

date, the bigger the gap becomes between the target and our actual

performance. Land-use regulations and road engineering standards

are often at fault, creating communities that separate homes from

commercial centres and schools, fragmenting natural areas, and

developing road infrastructure that favours the most efficient

movement of the automobile at the expense of pedestrian movement.

The environmental

impacts of such development include loss of fish habitat, dramatic

reductions in water and air quality, and downstream flooding of

precious agricultural lands, to name just a few. New research

from the Center for Urban Water Resources Management at the University

of Washington suggests that, when as little as 10 percent of the

watershed is covered with roads and roofs (impervious surfaces),

the fish decline. This is very bad news, because our research

shows that even low-density suburban development has 40 percent

to 50 percent impervious cover (Figure 6). By reducing the amount

of pavement on road surfaces and yards, the impacts on streams

and downstream agricultural lands can be dramatically reduced.

In our region, the majority of rainfall comes from very small

storms (less than 1” per storm, representing 54 percent of all

yearly rainfall). In this scenario, natural infiltration becomes

a very practical, realistic, and economic way of managing stormwater,

as the majority of water that falls can actually be absorbed into

the ground and returned to the aquifer and streams at rates that

maintain their natural function (Figure 7).

Economically, the

costs of conventional suburban development are becoming increasingly

high, both to the municipality and to the region. This includes

the alarming costs of flooding and erosion that have taken place

in past years on the agricultural lowlands due to increasing urbanization

of the uplands, and the replacement costs of infrastructure when

engineered systems fail. Our studies show that per unit cost of

alternative development (wherein for instance, streets use less

pavement, and natural drainage systems are used) can be up to

one-third cheaper than conventional development (Figure 8).

The East Clayton NCP:

The

East Clayton NCP was initiated in response to many of these issues.

The 250-hectare East Clayton site is located on the eastern border

of Surrey. As the map shows, the site is situated upland of the

region’s Agricultural Land Reserve and drains into three of the

region’s most significant water bodies (the Serpentine, the Nicomekle,

and the Fraser Rivers) (Figure 9). The NCP was conceived with

this regional context in mind. This mixed-use plan supports enough

of a variety of land uses and residential/community types to maximize

affordability, sociability, and availability of commercial services

within easy walking distance for the proposed population of approximately

13,000 persons (Figure 10). East Clayton has narrow streets; roadways

throughout the site use one-third less blacktop than do status

quo suburban sites. Stormwater management, consisting of yard,

street, and larger open space infiltration devices, will eliminate

nearly all downstream consequences of development. What is particularly

unique about this project is that no other initiative either here

or elsewhere has shown how a combination of efficiencies can dramatically

decrease site infrastructure costs while also reducing dependence

on the automobile. Due to the absence of examples that remotely

comply with these policies, it was important that the seven principles

provide a model that could be applied in other areas of Surrey

and in other municipalities in the region. Thus, Surrey City Council

endorsed the principles on January 25, 1999.

The

Seven Principles:

| |

1. Increase density and conserve energy by designing

compact walkable neighbourhoods. This will encourage pedestrian

activities where basic services (e.g., schools, parks, transit,

shops, etc.) are within a five- to six-minute walk of homes

(Figure 11).

Studies show

that if it takes longer than five minutes to reach basic

services, most people will choose to drive. But in order

for a store, even a small convenience store, to be both

viable and within a five-minute walk, it needs to be surrounded

by streets containing about 10 units, or twenty-five people,

per acre. The average overall density of East Clayton will

be between 9 and 10 units per acre (over twice that of conventional

suburbs). The density also seems to be the minimum for a

viable transit system. Eventually, a rapid bus will serve

East Clayton, providing connections (at 7-8 minute intervals)

to the larger municipality and region.

2. Provide

different dwelling types (a mix of housing types, including

a broad range of densities from single-family homes to apartment

buildings) in the same neighbourhood and even on the same

street (Figure 12).

Zoning has

been the single greatest instrument for segregating the

North American landscape according to class and income.

We realized that change could be brought about quite simply

by allowing different size parcels on the same street and

different family numbers and arrangements on each parcel.

With this in mind, the NCP provides a range of densities

and housing types. Housing will consist of low, medium,

medium-high and high density forms in detached, semi-detached,

fee simple row housing and town housing, and apartments

in the same neighbourhood and, where possible, on the same

street. A feature of most desirable neighbourhoods (Figure

13) is the tremendous degree of variety provided by houses

that address the street and that, by virtue of the size

of the lots on which they sit, and the diversity of tenure

type they provide, accommodate a mixture of family types.

Lots in East Clayton will be about one-half to one-eighth

the size of a typical suburban lot. In addition, secondary

dwelling units and suites, a feature of many of North America’s

older neighbourhoods, will be encouraged. The rental income

provided by the secondary unit will make homes affordable

while providing good housing in pleasant surroundings for

people who are beginning their careers, who don’t have sufficient

equity to buy a home, or who have other places in which

they would like to invest. Thus renters have a place to

live that is far more suitable, attractive, and integrated

than is the all-too-common and ever-increasing alternative:

being segregated by income into vast and featureless garden

apartment complexes, townhouse complexes, or low-income

projects.

3. Communities

are designed for people; therefore, all dwellings should

present a friendly face to the street in order to promote

social interaction (Figure 14).

Adhering to

this principle means never having to see a three-car garage

eating up the whole front of a house. Blocks in East Clayton

are to be proportioned to create a fine-grained, interconnected

network of streets. This interconnected network is fundamental

in reducing traffic, congestion, and allows as many homes

as possible the opportunity to front directly onto the public

street. The Plan inherently ensures more eyes on the street,

while creating a larger backyard for private outdoor space.

Tree-lined boulevards, infiltration devices and on-street

parking will buffer the pedestrian from passing traffic.

4. Ensure

that car storage and services are handled at the rear of

dwellings (Figure 15).

Where possible,

lanes will be provided at the rear of dwelling units in

response to existing site conditions, community structure

and lot size. This will ensure building fronts are not consumed

by garages and front yards consumed by concrete, contrary

to a pedestrian street which acts to engage the resident.

Again, the lanes allow cars to gain access to units from

behind, ensuring a minimum setback and a larger private

backyard area

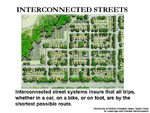

5. Provide

an interconnected street network, in a grid or modified

grid pattern, to ensure a variety of itineraries and to

disperse traffic congestion; and provide public transit

to connect East Clayton with the surrounding region (Figure

16).

Interconnected

street systems ensure that every trip may follow the shortest

possible route. Having a store within a five-minute walk

of your home is of no benefit if the five-minute walk requires

you to cut through three backyards and jump over five fences.

Yet most of our newer communities are designed to ensure

that virtually all trips are longer than they need to be.

Interconnected street systems (see Principle 4), can and

should give way to natural systems without compromising

the interconnected tissue of the local street system.

6. Provide

narrow streets shaded by rows of trees in order to save

costs and to provide a greener, friendlier environment (Figure

17).

‘Lighter, greener,

cheaper, smarter infrastructure’ is the opposite of the

‘heavy, grey, expensive, and stupid infrastructure’ we have

now. The gradual increase in the amount of pavement per

person, leading to the fact that the average suburban dweller

now has four times more pavement than does the average urban

dweller, has led to a corresponding increase in the impact,

per person, on both the environment and the public purse.

The way to save the environment, and money, is to pave less,

not more.

7. Preserve

the natural environment and promote natural drainage systems

(in which storm water is held on the surface and permitted

to seep naturally into the ground) (Figure 18).

If we want

to urbanize an area without destroying its streams (and

every last fish in them), then we must drain new neighbourhoods

in the same way that the original forests were drained:

through infiltration and evapo-transpiration. When rain

falls on a forest it adheres to the leaves, branches, and

trunks of trees. The precipitation that doesn’t evapo-transpire

on the trees flows into the ground. Virtually none of the

water runs over the top of the forest floor to the stream.

In a mature forest, about 70 percent of all the rain that

falls on it returns to the ground. Once in the ground it

either seeps slowly into the deep aquifers far below the

surface or into the shallow water table, where it flows

horizontally to the stream bank. This process of infiltration

may take a week, or a month, or six months to enable water

to through the ground and recharge the stream.

|

If you cut off this

shallow subsurface flow, then you cut off the lifeblood of the stream

and, consequently, destroy all the fish. To protect the stream,

and the fish in it as you develop an area, you must find a way to

maintain virtually all of the infiltration naturally occurring in

the watershed. All streams are simply the manifestation of the infiltration

performance of the soils in its watershed. So a city, as it builds,

must respect these soils and their streams by allowing them to continue

to perform together in the way they always have. Green systems are

an essential part of the East Clayton Plan. The initial 4-day charrette

process -- held in the spring of 1999 and used as a means of gathering

all interested parties around the same table to establish a shared

vision of the site -- resulted in a land-use plan that used existing

ecological systems as the plan’s basic armature.(Figure 19). Streets,

neighbourhoods, and land uses were structured around this green

framework. The Larger Picture: It bears discussing how the East

Clayton plan fits within the process of planning for the larger

Clayton Area. In 1998 Surrey Council adopted the Clayton General

Land-use Plan. As Figure 20 shows, the plan for East Clayton was

conceived with the entire Clayton area in mind; East Clayton would

be the most concentrated portion of this approximately 800 acre

area. The primary commercial area is located so as to create a true

“centre” for the Clayton community — at the corner of 72nd Street

and 188th Street. This area is envisioned as a Main Street area,

with street-oriented commercial, store-front offices and services,

and parking on the street (as opposed to on large paved parking

lots). Housing is also proposed above commercial locations so that

the area will remain lively and populated. At a finer grain, neighbourhood

commercial locations are proposed throughout the community as a

way of providing local, every-day services for residents within

a five-minute walk of their homes. A total of five neighbourhood

commercial locations a proposed throughout the community. These

locations are considered essential to providing easily accessible

and walkable services for local residents; they are also key to

achieving significant reductions in automobile use.

Conclusion:

In closing, it is important to re-emphasize that the East Clayton

NCP doesn’t exist in isolation; rather, its success is dependant

upon a coordinated and consistent approach to planning in adjacent

areas. One of most unique elements of the plan is the level of integration

that exists among the elements; eliminating one or two of the elements

results in a plan that is far less than the sum of its remaining

parts. Your original authorization to your Planning Department in

1999 was to “explore” the application of the seven principles to

East Clayton. This they have done, and done well. So if this Council,

in full recognition of both the opportunities and challenges that

lie before you, cannot support this sustainable approach, then the

exploration you authorized will have produced a useful result. You

will have discovered that the political and social costs of sustainable

development are too high for your city to pay. But we have every

reason to expect this Council to continue to lead the region. If

we had doubts we would not have worked with you for so long. Since

1995, UBC and its partners have provided nearly 10 person years

of effort for your various sustainability initiatives, all at no

cost to the City. We have been honoured to participate. As long

as your commitment to sustainable development remains as strong

as ours, we see no reason to stop. In our view, the East Clayton

project is the most advanced undertaking of its kind in North America,

and offers hope that we can create more affordable, livable, and

sustainable new communities.

|